FDA Guidance Shows a Regulatory Path Forward for Interoperable Devices

Market for interconnected medical devices is projected to grow but the regulatory pathway is still evolving. A new FDA guidance offers helpful recommendations for design and premarket submission.

Medical device industry is changing fast! Technology is driving rapid innovation and medical devices are becoming more interconnected, and smart! According to a 2018 Deloitte Consulting report, the market for interconnected medical devices is expected to grow from $15 billion in 2017 to $52 billion by 2025. This is very impressive growth rate in just 5 years.

One challenge confronting the industry is that the regulatory pathway for these inter-connected devices is far from clear. The technology is new, so there are not that many predicate devices. You will likely have to go through the De Novo process, where requirements are emerging on a case by case basis.

These devices use interoperability to connect with other devices to receive data, and in some cases, issue commands to deliver a drug or another therapeutic action. Interoperability basically means the ability of two or more devices to connect and share information. This connection can be hard-wired or wireless. When you use your phone to make a payment, you are using interoperability of the card reader at the kiosk. You can think of many other examples in your daily life.

One way to understand how FDA is thinking about regulating these devices is to review recently cleared devices. One such example is the Control-IQ technology, a software product recently classified by the FDA as a Class II medical device.

Another way is to review FDA guidance documents to understand FDA’s recommendations and expectations. In this blog, we are reviewing a guidance document issued by the FDA in 2017 which focuses on design considerations and pre-market submission for interoperable medical devices.

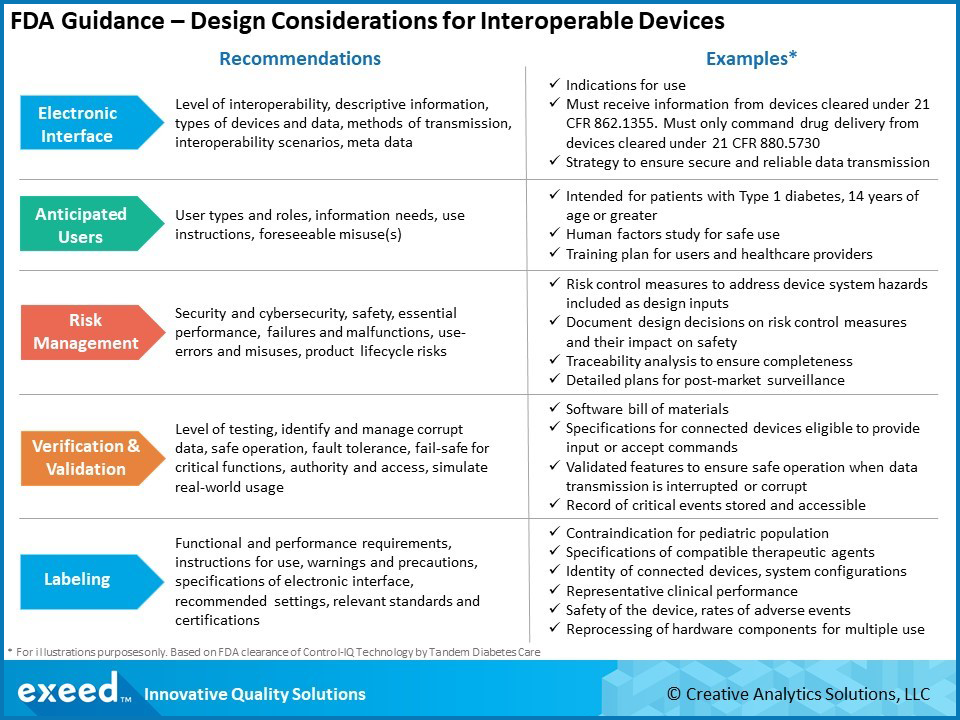

There are 6 key areas of focus in this guidance – Electronic Interfaces, Anticipated Users, Risk Management, Design Verification and Validation, Labeling and Consensus Standards. A summary of key recommendations and examples of FDA expectations are shown in the graphic below:

Unlike the medical devices of the past, interconnected medical devices have one or more electronic interfaces with other devices, either through hardware or a wireless connection. These interfaces provide powerful functionalities, but they also introduce new risks. FDA expects a clear definition of the purpose of these interfaces, including the type of data being exchanged and methods of transmission. Design requirements will directly relate to the purpose and associated risks. The interoperability scenario is important – for example, if the device is also issuing commands to another device based on data collected from a sensor, there needs to be proper time synchronization. Consistent units, for example metric vs. imperial, or appropriate conversion factors need to be used.

Thinking broadly about anticipated users of these interoperable, interconnected devices is important. In addition to the patient and their doctors, there are many other potential users such as network administrators, system integrators, equipment maintenance staff, IT professionals, etc. Determining the anticipated users helps in identifying foreseeable misuse(s) or use-errors so appropriate risk mitigating controls can be implemented. Human factors studies take on a new meaning and scope for these devices. Start early in the design process, work iteratively to finalize requirements and continue to follow during the post-market phase based on new information. Appropriate, user-specific, training may need to be developed in addition to device labeling.

As mentioned before, electronic interfaces in these devices introduce added significance to risk management decisions, including security and cybersecurity. It is a balancing act to allow authorized access, while designing security features to limit unintended access. Careful analysis of the balance between security and impact to functionality, usability and safety is needed. Product security, cybersecurity and safety teams must work collaboratively right from the start. FDA expects that an interoperable system should maintain basic safety and essential performance during both normal and fault conditions. As the number of interfaces and anticipated users increases, the number of potential hazardous situations also goes up. Therefore, a very comprehensive risk analysis is needed to support the design process by identifying all relevant design inputs. Risk considerations and mitigation decisions must continue throughout the product life cycle. This becomes particularly challenging because other devices that interface with an interoperable device may be from different manufacturers and may evolve in a way that creates unintended issues over time.

The extent and complexity of verification and validation will depend on the risk level, which in turn depends on the number and type of interfaces, their purpose and anticipated users. As is typical in any medical device design process, risk analysis drives design inputs, which in turn influences the verification and validation (V&V) activities. Additional considerations for interoperable devices include detecting and handling corrupt data, maintaining essential performance and ensuring fail-safe operation of critical functions. FDA also expects critical devices to also have a forensic capability by recording and storing information about critical events such as security breaches, data errors and transmission issues. Another consideration is the ability to update and patch software. Security by design is fast becoming a desired goal and a software bill of materials (SBOM) is now emerging as an expectation.

FDA recognizes that “one way to reduce risk and facilitate safe and effective medical device interoperability is to include in labeling the functional and performance requirements of the electronic interfaces”. Risk analysis should drive labeling considerations with particular emphasis on the electronic interface and anticipated users. The guidance offers several recommendations for labeling, especially in premarket submissions. These include details of the interfaces, recommended settings or configurations, instructions for IT personnel, warnings, precautions, contraindications, data specifications, etc.

FDA has recognized several consensus standards, but they continue to evolve. Standards help not only the device manufacturers, but also other stakeholders such as healthcare delivery organizations, including system integrators, system designers and IT professionals working in the healthcare environments. One reason for the rapid, astronomical growth of interoperable consumer electronic devices is the availability of common standards. In this respect, medical industry is still behind. As a result, there are significant challenges during the design process where different pieces of software often need to be stitched together because of a general lack of standards in this area. Refer to the FDA Recognized Consensus Standards Database for a current listing of standards applicable to interoperable devices.

In conclusion, interoperability holds the key to rapid innovation in connected medical devices. At the same time, technical standards and regulatory policy are still evolving. In this premarket guidance for interoperable medical devices, FDA has provided recommendations in 6 main areas: electronic interfaces, anticipated users, risk management, design verification and validation and labeling and consensus standards. Understanding FDA’s recommendations and reviewing recent examples of FDA cleared products can help you plan your product development efforts and premarket submissions.

References

FDA Guidance – Design Considerations and Pre-Market Submission Recommendations for Interoperable Medical Devices, September 2017

2018 Deloitte Report – MedTech and the Internet of Medical Things, July 2018

Control-IQ Technology – FDA Unlocks the Key to Innovation in Interoperable Medical Devices, February 2020