How FDA is Shaping a Regulatory Policy for Device Cybersecurity

Updated draft guidance provides recommendations for design, labeling, and premarket documentation. Industry response points to a long road ahead before it can be finalized.

Cybersecurity of medical devices is an emerging area of concern for both industry and the FDA. The 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack was a wake-up call, which showed how a simple backdoor hack through an outdated operating system could have a debilitating effect on thousands of connected medical devices in the healthcare delivery ecosystem. More recently, detection of the URGENT/11 cybersecurity vulnerabilities in the networking protocols used by many medical devices has underscored the potential for serious risks to information security and patient harm.

So far, there have been no reports of cyberattacks resulting in physical harm to patients. It seems the bad actors are targeting hospitals and other healthcare delivery organizations (HDO) for the financial value of their data. Still, the risk of harm to patients is real, as shown by 6 of the URGENT/11 vulnerabilities, which could be used for remote code execution to change settings on connected devices such as infusion pumps, patient monitors and MRI machines.

It is not a question of if, but when.

Cyberthreats to the healthcare delivery system are rapidly evolving. The frequency, severity and clinical impact of recent incidents continue to intensify. So far, the HDOs have been the target of cyberattacks, and now they are asking the FDA to hold device manufacturers more accountable. As a result, there has been a flurry of activity in this area – multiple cybersecurity safety communications, information-sharing agreements with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and other public-private organizations (ISAO), and guidance for premarket and post-market cybersecurity management.

A recent high-level FDA communication highlights the sense of urgency and provides a vision for a more robust regulatory policy.

“The CDRH cybersecurity vision is one where the medical device community takes bold action to transform medical devices from brittle to resilient. Every device would meet a security bassline; every device would be easily updatable; and patients would receive timely updates.”

FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner and CIO, CDRH Deputy Director

(FDA Communication, Nov 2019)

In 2014, FDA finalized guidance for pre-market expectations related to device cybersecurity. It was a short, 7-page, document with recommendations for cybersecurity functions to be considered in the design and development of medical devices, and documentation for pre-market submissions.

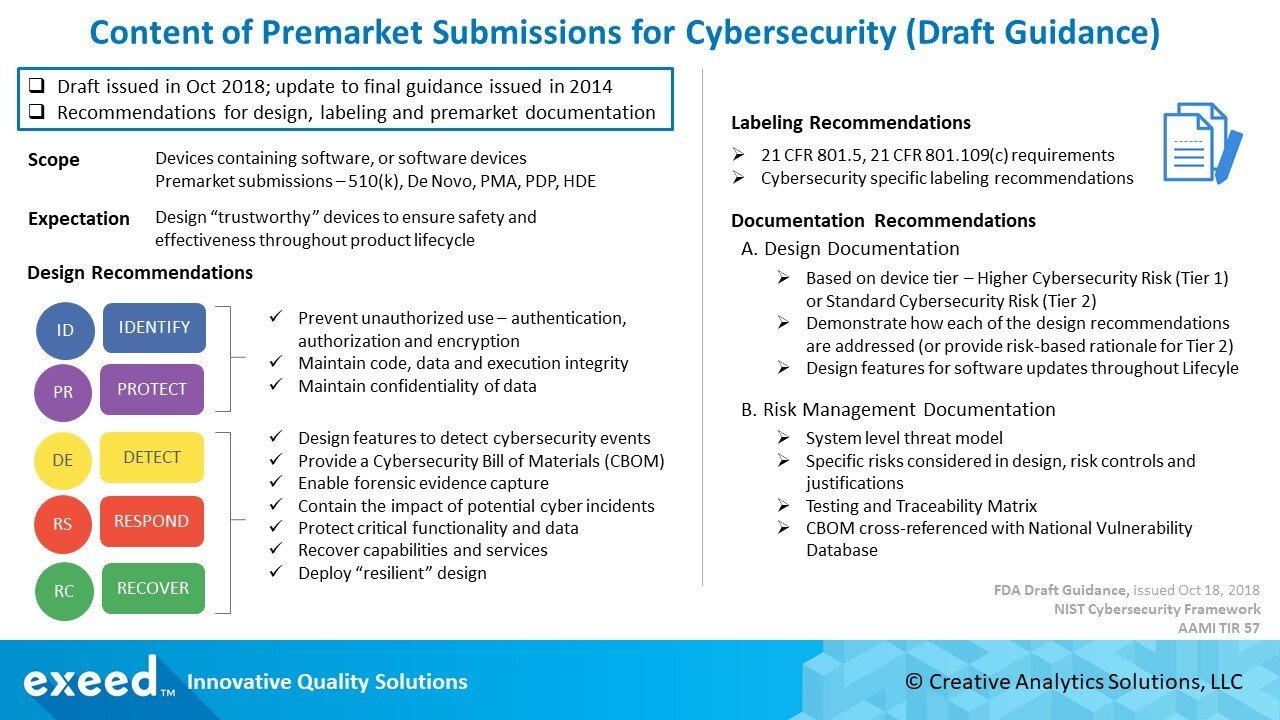

A lot has changed since then in the rapidly evolving cybersecurity landscape. There is more information about vulnerabilities and threats potentially affecting connected medical devices. Recognizing this new reality, FDA issued a revised draft guidance for pre-market submissions in October 2018. A much longer, 24-page document, this guidance provides many more specific recommendations for the design and development of medical devices, and documentation for pre-market submissions.

A summary of these recommendations is shown in the Figure below.

Response from the medical device industry and other stakeholders has been significant. Device manufacturers and industry groups have identified several areas of concern, which can be summarized under three main themes below.

1. Two-Tier Approach for Cybersecurity Risk Classification

FDA is proposing a two-tier classification for connected medical devices based on cybersecurity risk. “Higher Cybersecurity Risk” devices are considered Tier 1 devices, where a cybersecurity incident affecting the device could directly result in patient harm to multiple patients. “Standard Cybersecurity Risk” devices are Tier 2 devices; a broad, catch-all, category for all other devices that do not meet the criteria for Tier 1 classification.

There are several problems with this approach. It is inconsistent with the current statutory risk classification (Class I, II, III) and FDA recognizes the discrepancy. As an example, a Class I or a Class II device may be assessed to be a Tier 1 device for cybersecurity, while a much higher risk Class III device maybe Tier 2 for cybersecurity. The criteria are not clear and there is a significant opportunity for confusion in the risk classification of medical devices.

It seems the intent behind this two-tier approach is to help manufacturers in evaluating design requirement for cybersecurity, and in preparing documentation for premarket submissions. If a device is considered Tier 1, FDA will expect documentation to show how each of their design recommendations for cybersecurity has been addressed. Tier 2 devices, on the other hand, can utilize a “risk-based” rationale for why certain cybersecurity controls recommended in this guidance are not necessary. It seems to be a way to require more documentation for Class II devices beyond the current standard of showing substantial equivalence.

Understandably, the industry is concerned about this approach. Cybersecurity vulnerabilities present a set of hazards, which like any other hazard, may lead to harm. There is no need to utilize a special classification system just for cybersecurity. Instead, FDA should provide further guidance on expectations for cybersecurity risk assessments and expected controls. This can easily be accomplished within the framework of ISO 14971.

2. Cybersecurity Bill of Materials (CBOM)

FDA is proposing a CBOM that includes a list of commercial, open-source, and off-the-shelf software and hardware components that could be susceptible to vulnerabilities. The intent is to help device users (HDOs, patients, providers) understand potential vulnerabilities, assess the impact of any cyberattack and take countermeasures to maintain safety and performance.

The inclusion of hardware in this BOM is a point of concern for the industry. There is already an effort to standardize a software bill of materials (SBOM) and a consensus is emerging with the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). Adding hardware components to the list appears to be a significant burden for the industry. It will be interesting to watch how FDA responds to this concern and if they decide to drop this expectation or limit its scope.

Another concern, especially from the HDOs perspective, is the frequency of updates to the BOM and specific criteria around the use of outdated, unsupported software and hardware. There are already a lot of legacy devices in the market using such software and hardware components, which presents a significant uncontrolled risk.

3. Extensive Cybersecurity Labeling Recommendations

FDA is proposing an extensive 14-item list of labeling recommendations to communicate “relevant security information” to end-users. The list includes many technical design features related to cybersecurity such as features that protect critical functionality, description of backup and restore features, guidance for supporting infrastructure, features capturing “forensic evidence”, list of network ports, CBOM, etc.

Industry comments point to the 2014 final guidance, which only required labeling to include device instructions for use and product specifications related to cybersecurity controls appropriate for intended use environment (example – anti-virus software, use of firewall, etc.). The revised list appears to extend the regulatory authority of the agency, especially for devices seeking FDA clearance under a 510(k), as the predicate devices are not currently expected to meet these extensive labeling requirements. Industry concern is likely due to the broad scope of these recommendations where this information may not be available and may introduce excessively burdensome requirements during design and development. Instead, the industry is recommending FDA to focus on end-user communications to be more effective in addressing cybersecurity concerns and responding to incidents.

In Conclusion, the proposed draft guidance is facing significant concerns from the industry and a lot of work still remains to be done. Cybersecurity is such a new - and rapidly evolving - field that both industry and FDA are challenged to develop practical, effective solutions. The good news is that there seems to be a collaborative spirit around this “shared responsibility”. Industry comments, while critical of the proposed recommendations, do not sound defensive or adversarial. There are also many helpful suggestions for improvement.

In all likelihood, FDA will issue another revised draft guidance after reviewing these comments. Everyone wants the final result, but it is a good idea to take additional time to do it right.

Stay tuned!

References:

FDA Final Guidance (2014) – Premarket Submissions for Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices, October 2018

FDA Draft Guidance (Oct 2018) – Content of Premarket Submissions for Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices, October 2018

WannaCry Ransomware Attack – Frequently Asked Questions

URGENT/11 Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities – FDA Safety Communication, October 2019

FDA Safety Communications on Cybersecurity, October 2019